Come out of the front door of the St Andrew's Community building in the Liverpool district of Clubmoor, walk along the road and over to your left looms Anfield. It is a stadium that dominates the skyline and that feels appropriate.

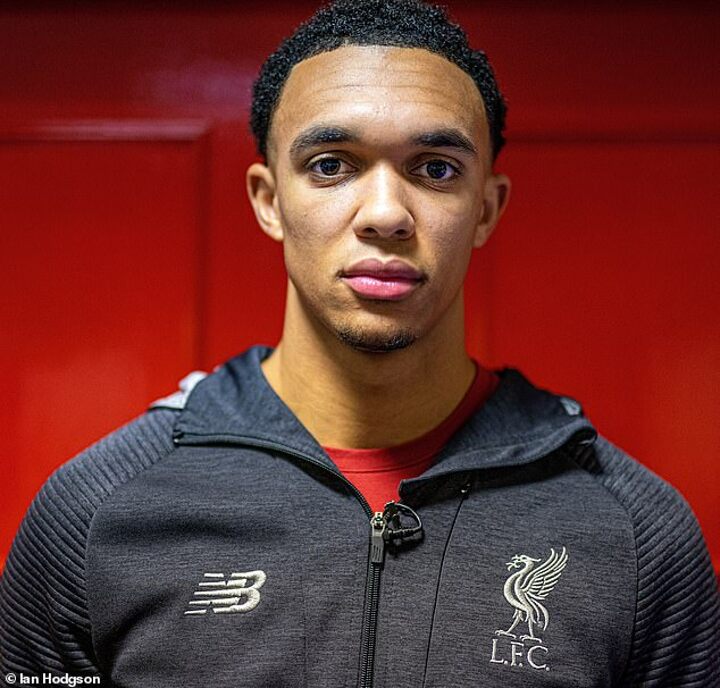

'That place is everything to the people round here,' Liverpool right back Trent Alexander-Arnold tells Sportsmail.

'You can't escape the football club here. It's overpowering.

'People here aspire to play for Liverpool and if they can't do that then they want to work for the club or be involved and support the club. You just have to look at it. You can feel it, can't you?'

Liverpool has been in Alexander-Arnold's blood since he was born and brought up round the corner.

'I went to school just over there,' he points. 'My brother played for teams on pitches just across the road. As for this place, I would drive past it every day on my way home.'

St Andrew's is a modest, unremarkable building. But it's an important place. It serves as a foodbank for North Liverpool and 25 per cent of the food that ends up here is donated before and after Liverpool and Everton home games.

People in areas like Clubmoor and Anfield rely on places like St Andrew's for food, support, advice and friendship.

Alexander-Arnold was told as a young kid by his mother Dianne that community was everything.

'This is where I grew up so places like this are important to me,' the 21-year-old says. 'It's disappointing to know this still exists because it means something isn't right in our country. But seeing how hard the guys here are working to make sure other people can have a hot meal over this winter period is great to see.

'It inspires me to keep doing things in the community as people are suffering. Everyone in life should have a fair chance. Places like this are not talked about enough. I would imagine there are hundreds up and down the country. They need recognition.'

On Wednesday night at Anfield, Liverpool meet Everton in the Premier League. Liverpool are superior on the field, but off it the clubs are equal. Everton are supporters of the St Andrew's food bank too.

Tuesday marked the start of Liverpool's Christmas food bank appeal and fans of both clubs will be able to drop food donations off at the stadium before and after kick-off this evening and at forthcoming home games. There is also a text number that enables supporters to donate money.

'This is a city of two great teams and the rivalry will probably help the food bank,' smiles Alexander-Arnold. 'One set of fans doesn't want the other one to be seen as more generous or more giving.

'They will be competitive about it. That's the way the people in the city think so hopefully St Andrew's and the people who rely on it will benefit.'

Alexander-Arnold has half an hour to talk before he must leave for an afternoon training session round the corner at Melwood.

When he was a kid, he was one of the ones standing on wheelie bins or peering through cracks through the fence to catch a glimpse of Steven Gerrard or Jamie Carragher. From the age of seven, he was being told he could be good enough to make it, too.

The first game he watched as a boy was the Champions League quarter-final against Juventus in 2005. He was six years old. 'That Juventus game changed the way I thought about football,' he says.

'I was intoxicated by what I saw and felt that night. From seeing the bright lights, the kids waving the Champions League flag in the centre of the pitch, the music. That changed everything for me. I realised that night it was something I wanted to be involved in for ever.'

The 2005 Liverpool team was a good Liverpool side but it was not on a par with this one. Ahead of Wednesday night's game they have won 13 and drawn one of 14 league games. Liverpool have not been at their best this season but are capable of playing breathtaking football.

On my mobile phone I show Alexander-Arnold footage of a great Liverpool goal scored by Terry McDermott in a 7-0 thrashing of Tottenham in the late 1970s.

A move that went flank to flank courtesy of David Johnson and Steve Heighway eventually ended with McDermott heading in at the Anfield Road End.

I ask Alexander-Arnold if it reminded him of anything. 'Yeah,' he smiles bashfully. 'Somebody showed it me after the Man City game recently. It's a bit like the one we scored.'

The goal in question was Liverpool's second in what still feels like a pivotal 3-1 defeat of the Premier League champions last month. It went, Alexander-Arnold, Andy Robertson, Mo Salah.

'It's great for people to say it's similar,' Alexander-Arnold adds. 'It's very flattering because they were great players back then. The one we scored was a fantastic goal with so many different parts to it and obviously the excellent finish.

'The reason me and Robbo switch the ball across the field that much is because as full-backs you understand how it feels when teams do that so quickly to you. Having to shift so much is exhausting. There is so much running involved, an extra 30 or 40 yards to try and close it down. It creates space. That's the idea.'

Alexander-Arnold and Robertson — another regular visitor to St Andrew's — are crucial attacking outlets for Liverpool. At times they appear to have limitless energy. Maybe it's just called youth.

This season it feels like there is more to come from Jurgen Klopp's team. After the weekend's win against Brighton defender Virgil van Dijk suggested there is another 10 per cent in this side. Maybe there is actually more?

'Yeah, we are nowhere near 100 per cent,' Alexander-Arnold says. 'I am not sure we have had a game yet where we have been happy with our performance. The City game was excellent but even then we were disappointed that we conceded. It's hard to accept but for us it's about winning.

'You don't get given anything for pretty football, do you?'

Liverpool's response to last season's second-place finish has been exceptional but Alexander-Arnold believes the disappointment of ending with 97 points and nothing will not be erased until they actually win the league.

Previously he said he felt he 'let everybody down' last season and adds: 'Yeah, we got all those points but it wasn't enough was it?

'We got all the fans' hopes up and played outstanding football but ultimately we didn't get there, we disappointed them. It doesn't matter how it happened or how we lost it. We could have lost the last five games or won them all, as we did, and it wouldn't really have changed anything. It was still the same disappointment.

'We wanted to win it so much and the fans wanted us to win it so much but we couldn't do it.'

It feels as though Liverpool are two-thirds of the way to making good that disappointment already but Alexander-Arnold reminds us that there are 24 games left.

'Last season City won the last 14 or 15 games on the bounce and they can do it again, can't they?' he asks. 'It's hard to get too excited right now.'

The mural of Alexander-Arnold outside Anfield is a wonderful thing. It just says: 'I am just a normal lad from Liverpool whose dream has just come true'.

Still living at home with his mum — 'I have no plans to change that' — there certainly is an air of normality as he chats with staff at St Andrew's.

Of all the Liverpool players, he makes the most community appearances. But there was a time when his future at Liverpool was threatened by problems with his temper.

Having come through the ranks from the age of seven — even swapping schools to one that would allow him time off to train in the afternoons — he reached the periphery of the first team as a teenager only to be told he was in danger of throwing it all away.

'I couldn't control my emotions well enough and it was having a negative impact on me and the team,' he recalls.

'I would give a goal away or make a mistake or if I didn't agree with a referee's decision, I would lose my head. In training and in games. We would effectively be down to 10 as my head would go. I would be diving in to tackles trying to get my emotions out.

'They told me the mental side was going to stop me making it. So they just worked on me. It was probably the worst season I had in terms of the environment I trained in and how hard it was.'

Neil Critchley and Alex Inglethorpe were the Liverpool coaches who hustled and cajoled Alexander-Arnold through that difficult time four years ago.

'Alex and Critch were just hammering me every day,' he says. 'If I made a mistake they would laugh. They would stop training and make the best player go one on one with me. If he got past me everyone would cheer.

'They were putting me in a harsh environment to try and better me and make sure I was ready to make that step up. They said that over the next few years the aim was to get me in to the first team as right back but that if I didn't get on top of my emotions there is no way the manager would like or want me.'

Alexander-Arnold was booked on his first-team debut in October 2016 but has only been cautioned 12 more times in more than 100 subsequent appearances. He has never been sent off.

'I used to think a mistake was the end of the world,' he says. 'Now I think that if I learn from it, then it's fine. Different players channel emotion in different ways. I have really mellowed it down.'

A first-team player for just three years, Alexander-Arnold has only really known good times at Anfield. But that doesn't mean a long-standing fear of failure and rejection has totally dissipated.

'Maybe some of that will always remain and that's not a bad thing,' he says. 'I used to train with the first team but always feared being placed back down in the academy again. I almost thought it would be embarrassing for me.

'I wanted to stay up there and learn from the seniors as I always thought it could end any minute and I would be back down again.

'After each session for about three or four months, (assistant manager) Pep Lijnders would come in to the reserve changing room and say, "Yeah, you are back with us again tomorrow".

'I always thought I would go back down so it helped because every day I trained as though it was my last one up there. Then I came back from an international break and went to get my kit and was told it was in the first-team changing room. I went in and suddenly I had a locker. That was the time I thought, "Yeah, the manager likes me".'