The closest Pep Guardiola and Jose Mourinho came to socialising when the two were Manchester rivals and near-neighbours came at Tapeo & Wine, Juan Mata’s restaurant in Deansgate.

There is a small downstairs room, available for private bookings, where Manchester’s foreign football community relax and watch games together. One night Mourinho was dining there, until he learned that Guardiola and his entourage had it booked. Mourinho left quickly to avoid any awkwardness.

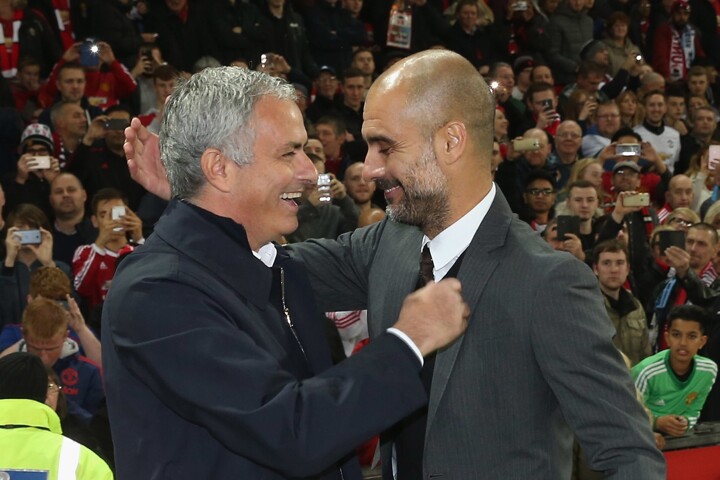

This time, it was a rivalry that never quite took off. Those two and a half years the pair spent competing in Manchester, and living round the corner from one another, was ultimately a disappointment. Everyone hoped for England’s own equivalent of those two seasons when Guardiola managed Barcelona and Mourinho led Real Madrid, perhaps the greatest club rivalry of the 21st century, at least until City and Liverpool came around.

Arrigo Sacchi described that spell, across the 2010-11 and 2011-12 seasons, as like having “two Picassos in the same period”. It was a rare example of having the two best teams in the world and the two best managers — as well as the two best individual players — on opposite sides of the same divide. And with each of the teams representing the perfect embodiment of two polar opposite conceptions of how football should be played. Guardiola’s Barcelona took possession and pressing to new levels, Mourinho insisted that great teams did not need the ball to win.

Mourinho had been brought to Madrid in 2010 with the explicit purpose of knocking Guardiola off his perch. It did not start that way, Barcelona winning the first Clasico against Mourinho’s Madrid 5-0, a personal humiliation for a manager just six months after he won a historic treble with Inter Milan.

It did not take long for the rivalry, initially ideological, to become bitterly personal, during a draining run of four Clasicos in 16 days in April 2011.

Ahead of the Champions League semi-final first leg, the third of the four matches, Mourinho targeted Guardiola’s perceived hypocrisy and sanctimony over referees, mentioning the luck he had enjoyed with referees in the past. Mourinho said that, until this moment, managers could be divided into groups. “The small one comprises those who don’t talk about referees at all. And the other huge one, in which I figure, is made up of those who only criticise referees if they make important errors. But now there is a third group with only one member: Pep. It is a new group, never seen in world football, somebody who criticises a referee for getting it right.”

When it was Guardiola’s turn to speak he was advised not to engage with Mourinho’s barbs but instead he met them head on. He started with an epic two-and-a-half minute answer, pointing out that in his mind the only true victories were on the pitch, rather than in the media. And he said he was happy to cede that PR victory to his rival. “In this particular press room,” Guardiola snapped, “he is the fucking boss, the big fucking chief. I don’t want to compete with him in this arena for one instant.”

This remains, almost nine years on, the most personal and explosive attack of Guardiola’s career. And it came with a tinge of sadness, too, as Guardiola reminded Mourinho of the four years they spent together as young men at Barcelona. He even had to correct himself when he referred to their “friendship” there. “No, not quite friendship, but working relationship.”

The two men did have to work closely together at Barcelona back when Bobby Robson and then Louis van Gaal were managers.

Robson brought Mourinho, his translator, to Barcelona when he replaced Johan Cruyff as manager. Mourinho was an ambitious and intelligent 33-year-old just making his way in the game. Guardiola was only 25 but he was one of Barcelona’s senior players. As detailed in Jonathan Wilson’s book The Barcelona Legacy, Guardiola was part of the ‘Gang of four’ along with Luis Enrique, Sergi and Abelardo. Mourinho knew that to be an effective go-between between Robson and the players he had to get close to Guardiola. So he did. And when Barcelona won the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1997, beating Paris-Saint Germain 1-0 in the final, the two men triumphantly embraced on the touchline.

Eventually their careers diverged as Mourinho went into management, not adopting the classical Barcelona style but something akin to its opposite. Mourinho was already established as the best in the world, with a Champions League at Porto and two Premier Leagues with Chelsea, before Guardiola had managed a senior game. And so Mourinho was painfully stung in 2008 when the Barcelona board went for the untested 37-year-old over him as manager.

That was one of the most important decisions in football history, giving Guardiola the platform to change the game — and Mourinho a grievance. Two years later they were competing in Spain as equals. But not many would say that now, as they prepare to meet on Sunday at the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium.

Guardiola has spent the last decade still on top of the world game. His Bayern Munich team set new standards even if they did not reach a Champions League final. At Manchester City he has done the same, setting the two highest points totals in Premier League history, even if those records might soon be broken by Liverpool.

Mourinho is not in the same position he once was. At Real Madrid he won one league title and left after three stormy years. In a second spell at Chelsea he won one league title before the team collapsed and he was sacked just before Christmas of his third season. At Manchester United he won trophies but not a league title before being sacked after almost the same amount of time. For all the hopes that City and United would be like Real Madrid and Barcelona, they were not equal enough to be serious competitors. Mourinho knew quickly enough that City had a superior machine and superior resources to him. Over Mourinho’s two-and-a-half-year spell at Old Trafford, 93 Premier League games each, Guardiola’s City won 46 more points than United.

That, in a number, is why Mourinho has had to take a step down to manage Tottenham this season. Florentino Perez still admires him but he has not built a team that could claim to be Europe’s best for years now. He has clearly lost his role as Guardiola’s great rival to Jurgen Klopp.

But all that raises another possibility.

If Guardiola and Mourinho are no longer competing for the same space, or trying to prove the ultimate superiority of their idea over the other’s, then that might provide the room for a late-career detente between the two men. Like between Arsene Wenger and Sir Alex Ferguson, who were furiously at each other’s throats in the late 1990s after Wenger showed up determined to unseat United. But by the end of their tenures, especially when Arsenal’s challenge had been supplanted, the two men became close. The realised that that they had too much in common, in outlook and age and values and shared experiences, to keep on sniping.

Guardiola and Mourinho are not at that point yet — Guardiola has only just turned 49 — but it is likelier that the Spaniard’s best achievements are behind him rather than in front of him. And on Sunday he might look at Mourinho, 24 years after they met in Barcelona, and see a familiar face, someone he worked with and won with, and who reminds him of his youth, rather than the “fucking boss” of the Bernabeu press room.