More than a century on from the acrimonious split which led to the formation of one of British football's most successful clubs, and enduring rivalry, the argument is still simmering.

Liverpool and Everton meet at Anfield on Sunday in the 232 Merseyside derby. It is the most played, most enduring – and in recent years most ill-disciplined – derby match in English football.

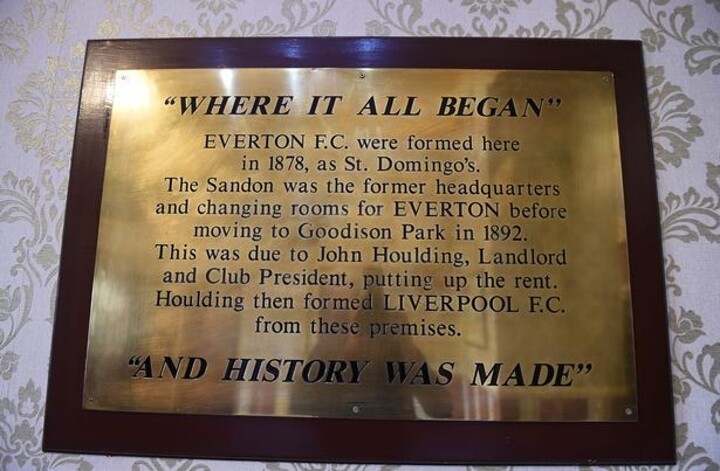

And it was borne from the most famous rent row in football history.

Almost every supporter who crams into Anfield this weekend will be aware that Everton originally occupied that stadium, but left to cross Stanley Park and build a new ground following a row with landlord John Houlding.

But their appreciation of that local history will probably be coloured by their allegiances.

To Evertonians, capitalist John was a Tory chancer who tried to make a fast buck out of Everton Football Club's growing popularity.

To Reds fans, ‘King John’ was a noble benefactor and Everton were the cheapskates who failed to pay their rent.

As ever, the truth is somewhere inbetween - and heavily nuanced.

This week a long overdue bust to John Houlding was unveiled at Anfield, symbolically looking up in awe at the colossal arena Anfield has become.

The ceremony took place 127 years after the original row started, and 116 years after the former Lord Mayor of Liverpool passed away in the South of France following a lengthy illness.

At his funeral players from Liverpool AND Everton symbolically carried his coffin.

But by 1902 tensions between the clubs had long since eased.

That was not the case in the autumn of 1891 when Liverpool was home to just one First Division football club, the reigning champions of England, Everton Football Club.

We take a look at what actually happened either side of Christmas 1891, and what really led to the formation of one of English football’s greatest rivalries.

THE PLAYERS

The Future Reds

John Houlding: A landowner and self-made businessman who made his fortune as a brewer. And President of Everton Football Club.

Edwin Berry: Houlding’s ally on the Everton board, and a solicitor to the Licensed Victualler’s Association.

John McKenna: A friend of Houlding's who had moved to Liverpool from Ireland in the 1870s seeking work and became vaccination officer for West Derby.

William Barclay: Another Irish immigrant and friend of Houlding's.

The Future Blues

George Mahon: The organist of St Domingo’s Church and a member of the Liberal Party which, despite the name, was the party of moral purity in the austere Victorian age.

Rev Ben Chambers: Loosely described as the founder of Everton, was a prominent member of the Temperance Movement and once took a pub to court in Stoke for breaking a licencing law.

(Everton President, Sir Philip Carter, author Peter Lupson and Liverpool chief executive, Rick Parry by the restored grave of both clubs' founder, Rev Ben Chambers.)

Dr Clement Baxter: A committed and much loved city doctor who regularly witnessed first hand the appalling affects of drink on his patients – and a Liberal councillor to boot. (Incidentally current Everton director Jon Woods is a direct descendant – Everton is the only one of the Football League’s original 12 clubs still with direct links to their founding fathers).

Will Cuff: A choirmaster at St Domingo’s, a strong and committed Christian who once declared that: “Football is the greatest teetotal agency in the world.”

William Whitford: An active temperance campaigner who went around talking about the “iniquitous influence of brewers” at a time when Houlding still owned his club!

William Clayton: A committee member who used to give regular temperance talks to a Formby church.

Clearly there were already two factions on the Blues board - zealous moral puritans, and men who had made their money from drink.

THE TENSIONS

Ultimately money, as always, was at the root of the row, but the backgrounds of the combatants cannot be under-estimated.

In a sparkling 2009 lecture at the Hornby Room in Liverpool’s Central Library, historian Peter Lupson said: ““The Temperance Movement was at its height in the 1880s.

“There is no doubt that had Houlding been a butcher or a baker, he would have had no problems.

“But he was a brewer.

“And at the time the association with drink was something that people of high moral standards were strongly opposed to.”

And the majority of the rapidly expanded Everton board were tee-total.

Indeed when Mahon ultimately led Everton to Goodison Park he ensured it was a club policy decision not to sell intoxicating liquor on the premises and that brewers would not finance the club.

Chang would have bee sent packing in 1892!

But that’s getting ahead of ourselves. First the background …

EARLY DAYS

John Houlding, initially, was an Everton saviour.

When Everton were forced to move from Priory Road to Anfield in 1884, evicted because of the size of the crowds they were attracting to an arena which is now the site of a petrol station, the club’s very future was threatened because of the cost of building a new stadium.

Two members of the management committee, William Barclay and W Jackson went to Houlding, a wealthy businessman and sports lover, and asked him to buy the club out.

The cost of building a new stadium was £6,000 – in an age when £1,000 would have paid the wages of an entire football team for a whole year.

Houlding was offered no guarantees, with just a maximum of £100 a year rent in return, but he agreed so that Everton could continue.

In 1889 when he opened his second pub – he already had the enormously successful Sandon Hotel near Anfield - he introduced free Christmas dinners for the elderly and poor in West Derby with, eventually, 1,000 beneficiaries.

He was also involved in a workhouse and opened an orphanage in Fazakerley.

So not the pantomime villain he was later portrayed?

THE TIMELINE

The quite magnificent “Play Up, Liverpool” website – a wonderful work devoted to the history of Liverpool Football Club – has collated every worthwhile newspaper cutting of the day – whilst remaining acutely aware that in the Victorian era newspapers had agendas and political slants as much as today’s media.

Their collection details the escalation of the row accurately.

First, the Anfield back story

Joseph Orrell inherited the lad on which Anfield was built from his father in 1883 and put it up for sale in 1885.

Houlding bought it, for the use of Everton Football Club, for £5,228, 11 shillings and 11 pence, with legal costs rounded up to £6,000.

Houlding handed over £2,000 of his own fortune – and took out a mortgage to pay the rest paying 3% interest.

The contract also stipulated that Houlding should make an annual donation to Stanley Hospital in Orrell’s name – and, crucially, that land adjoining Anfield, owned by Joseph’s uncle, John Orrell, should never be developed in case an access road was ever needed to be built there.

Now, to the, action ….

May 15, 1891 - Money matters

Just seven days after Everton had been presented with the Football League Championship trophy for the first time an AGM was staged at College Hall in Shaw Street.

But in amongst preparations to display the trophy prominently in shops on Church Street and Lord Street, there were murmurings about financial expenditure.

John Houlding replied that he simply received 4 per cent of the money he had invested in the ground - £6,000 - adding that when the club first started he only got one per cent and, looking at its flourishing condition now, he naturally expected more.

September 15, 1891 – Staying power?

The Liverpool Mercury reported on a meeting of members of the Everton club at the Lecture Hall , Everton Road, when growing tensions were evident.

Everton were regularly attracting gates of of 14,000 and 15,000 to Anfield. The club was clearly benefiting financially, but Houlding was still receiving just £250 a year rent for use of his ground.

John Houlding proposed to convert Everton club into a company, in order to raise capital for the club to purchase the stadium.

William Clayton opposed the scheme and, according to the report “it was evident from the reception he received at the end of his remarks that he had the sympathy of the meeting.”

Were the tee-totallers starting to break ranks with the brewers?

September 21, 1891 – We shall not be moved

Another meeting, attended by around 300 of the club’s 500 members, debated the issue again.

Again the majority were unhappy at seemingly being “coerced” into Houlding’s scheme.

The Mercury reported: “Everton as a club are not rooted to the particular piece of soil upon which they now cater football. The club has made a name, and has a host of enthusiastic followers, who as one speaker said, would patronise the game whether played at Fairfield, or even the Dingle. The better plan would be for those who disagree with the committee’s scheme to form a committee among themselves, to make inquirers and present alternate schemes.”

September 24, 1891 – Problem solved?

As quickly as the row had started, it appeared to be resolved.

The Daily Post reported that “an amicable arrangement will shortly be arrived at on the matter in dispute between the Everton club and the proprietor of part of the ground Mr. John Orrell.

“Mr Orrell it is stated, has intimated that he is ready to accept £120 a year rental for his portion of the land.”

The report concluded, somewhat optimistically that: “The proposal will come before the committee of the club and there is little doubt that it will receive their sanction.”

In effect, the Everton board was expected to agree to pay £250 to Houlding and £120 to John Orrell.

But Houlding’s supporters were unaware that George Mahon was already investigating a new site across the park, which could be developed at a cost of £50 per annum!

Some of Houlding’s opponents believed he was keen to remain in the area because of the considerable takings the proximity of a football stadium to the Sandon Hotel generated.

It was also a matter of some concern to some board members that the team continued to change at the Hotel and walk 100-yards, through the crowds, to the stadium!

Houlding, of course, denied that the Sandon had any part to play in the dispute.

October 10, 1891 – The gloves are off

Ahead of another meeting of the club a pointed circular was issued to members.

It included the paragraphs ….

"Rent: – Mr. Houlding demands £250 per annum notwithstanding the fact, that Mr. Orrell’s demands has arisen entirely through Mr. Houlding’s inability to give us peaceable possession of the land which he (Mr. Houlding) has been and is now charging rent for lease – he will not say that he will grant one.

"Alternative schemes- we are not without these and they will be fully disclosed and handed to your committee at the proper time.

"We have obtained for your information particulars of rentals paid by others clubs, and now append list of same – Aston Villa £175, Notts County £186 (stands included), Police Athletic £80, Bootle £80, Burnley £75, Stoke £75, Blackburn Rovers £60, Darwen £50, Wolverhampton Wanderers £50, Sunderland £45, Accrington £40, Bolton Wanderers £35, West Bromwich Albion £35, Preston North End £30, Liverpool Caledonians £25, Everton Mr. Orrell £120, Mr. Houlding £250, total £370.

The above figures need no comment.

"The circular was signed by

"William Clayton, 74 Dacey-road

"George Mahon, 86 Anfield-road

"And endorsed by J. Atkinson, Dr James Baxter, Abraham Coates, Frank Currier, J. Griffiths, W. Jackson."

Battle lines were clearly being drawn.

October 12, 1891 – Houlding firm

A row which had simmered up until this point erupted at a meeting in the lecture hall of the College Hall , Shaw Street.

It was reconfirmed that Mr Orrell would not disturb the club provided he was paid £120 a year, in advance, for 10 years.

It was reconfirmed that Mr Houlding would not deviate from the £250 arrangement he had entered into on the 24th July 1888.

George Mahon's response was to move that the committee instruct a solicitor on behalf of the club, to serve notice on Houlding to quit the present ground.

Houlding had different ideas.

He served notice on Everton to quit Anfield!

He delivered the bombshell that John Orrell had served notice on him of his intention to build the access road on the north side of the stadium, encroaching on 18-feet of the stadium – pointedly 18-feet on which an enclosure and stand had been constructed!

Houlding wrote: “I am required by Mr. Orrell to remove them forthwith. Under these circumstances, it is with extreme regret that I am obliged to give you, notice, which I hereby do, that you must give up possession of the piece of land, situated between Anfield Road and Walton Breck Road, used as a football ground, with the approaches thereto, after the closing of the present season, namely on the 30th April 1892.”

From that point on there was silence. Publicly at any rate, until a series of meetings in late January 1892, presumably as both parties considered their options.

January 25, 1892 – All friends again?

Meetings, on January 23 and January 25 - were boisterous, often ill-tempered, and contained claims and counter-claims of how much each party would be prepared to pay to remain at Anfield.- and how much cheaper a new option on Goodison Road would work out.

But they appeared to have ended on an amicable arrangement.

Houlding’s rivals pointedly claimed: “In addition to the land, we are offered a large house adjoining the ground, tenant of which is about to leave. This house would be suitable for dressing-rooms, offices, and club house for members.”

In other words players would no longer have to change in a pub!

At the January 25 General Meeting William Clayton proposed that “That the Everton Football Club offer Mr. Houlding £180 rental, and Mr. Orrell £100 a year for his portion of the land, on a lease to run for ten years.

“As a business man he would prefer to get the Goodison road ground at £50 a year. However, to save time, and because it was desirable to remain on the present ground if possible, he would propose the resolution he had read, with the addition that if Mr. Houlding refused the terms the committee should be empowered to secure another ground, Goodison Road for preference.”

Upon the vote being taken, Mr. Clayton’s motion was adopted almost unanimously.

Mr. Mahon then proposed that the Goodison Road ground, should be secured by the committee if Mr. Houlding refused the offer.

The resolution was carried by all but four members.

Mr. Clayton then moved “That the club be turned into a Limited liability company, to be called “The Everton Football Club Limited,” .

Again the resolution was carried.

The split appeared amicable.

Mr. Clayton moved a vote of thanks to the chairman, who in replying, said that would probably be his last connection with the club.

He believed every person present had acted under the most conscientious motives and he trusted they would give him similar credit (applause). He did not agree with the step they had taken and he believed they had taken a leap in the dark.

He had been connected with the club for a long time, and had helped it through many difficulties, a statement which drew warm applause.

He was also prepared to help them in their present difficulty, but in a different way to that upon which they had decided.

The resolutions passed made the matter too serious a one for him to undertake and he was afraid he would have to send in his resignation as chairman of the committee. In conclusion, he hoped the club would be successful, and that the members would have “A Happy New Year.”

What's in a name?

It was Bill Shankly who claimed there were only two teams in the city, Liverpool and Liverpool reserves.

But when Shanks’ dad was barely a glint in his father’s eye, there were two Everton Football Clubs in the city!

Barely had the bonhomie of the night before died down than Houlding had moved to register a company under the title ”Everton Football Club and Athletic Ground Company, Limited” with its headquarters listed as Anfield Road.

There were six members

A.E. Berry , 62 Dale-street, Liverpool

J. Houlding , Stanley House, Stanley Park

A. Nisbet , 13a Erskine Street

J.J. Ramsay , 7 Hawkesworth Street, Anfield

J. Dermot ,66 Norwood Grove

W.E. Barclay , 158 Adelaide Road

J. McKenna , 28 Nuttall Street

Houlding didn't just want a football team playing on his ground, he also wanted a team called Everton playing there.

The Liverpool Mercury reported that “the minority members of the present club mean to remain at their old quarters and have already floated a company under the title ”Everton Football Club and Athletic Ground Company, Limited” , registered in Somerset House.

“It is quite certain that the Everton Football Club will deny the new company any right to lay claim to a portion of the title which they have assumed.”

The national Field Sports magazine, however, seemed strangely behind Houlding’s camp.

A correspondent wrote: “Mr McKenna was the only real opponent of Mr Clayton during the evening, but his utterances were not to the liking of the members, who frequently interrupted him.

“Mr McKenna was listened to with but scant courtesy, as he subsequently attempted to show that the initial cost of draining and equipping the Goodison Road ground would be so great as, even spread over a number of years, to saddle the club with a larger rental than Messrs. Houlding and Orrell were now jointly asking.

“Once when speaking of Goodison Road, Mr. McKenna used the profane expression, “God forgive me for calling it a road. It is not even made ground. ”

No Goodison?

Another pro-Houlding report in the Field Sports magazine suggested that the FA would almost certainly agree to Houlding’s group retaining the “Everton” name – they didn’t – and that it was highly unlikely a new ground could be constructed on Goodison Road – it was.

Their correspondent wrote: “ Because Mr. Houlding had already taken legal possession of the name, which, combined with the fact that the club, is still to be carried on at the old headquarters , will doubtless have due weight with the English Association and the Football League when the question of official recognition comes to be fought.”

It also cast doubt on the chances of the breakaway band building a new stadium at Goodison Road.

“Mr. Houlding will naturally retain possession of the stands and other erections at Anfield Road,” it went on “and this will enormously increase the cost involved in putting the Goodison Road site in fit condition for football – a project which may possibly not be undertaken after all now that events have taken an extraordinary turn.

“Apropos of Goodison Road , a few facts relative to that ground may not be without interest.

“Besides the expense of putting up stands , the drainage and boarding of the ground would entail an expenditure of at least £600; whilst over and above that two feet of soil would have to be deposited on the ground to make it suitable for the purpose of football.

“It has frequently been stated that the club might secure a lease of the ground from seven to twelve years.

“We are in a position to state that under no circumstances would a lease of more than seven years be granted.”

One hundred and 26 years later the Blues are still in residence.

But The Field Sports correspondent still hadn’t finished.

“It may not also be generally known that a firm of brewers have agreed to guarantee the rent , board the ground , and erect stands provided that they are at liberty to control the entrances as they choose – a stipulation which means that the entrances will be placed as near as possible to the public houses in the vicinity.”

Was the Field Sports correspondent being briefed?

And if so, by whom?

February 1, 1892 - Houlding the upper hand?

Field Sports was nothing if not consistent.

A week later they wrote: “ In establishing a new company and registering it under the new title of ”Everton Football and Athletic Ground Company, Limited” , Mr John Houlding has unquestionably gained the upper hand in the dispute.

“Both the League and the English Association are certain to look at the broad facts that the Everton club is still conducted at the old headquarters, and that it will receive their official recognition may be regarded as practically settled.

“The one great result of the controversy seems likely to be the present hand of malcontents, and the carrying on, of the old club in future by those intimately acquainted with its early vicissitudes and troubles.

“That a club could ever flourish at Goodison Road unless backed by the most powerful financial aid is altogether out of question. And I doubt whether Messrs. William Clayton and George Mahon and their supporters have realised the enormous expense certain to be involved in the removal to Goodison Road .”

Maybe Field Sports failed to realise the drive and determination of Messrs Mahon and Clayton!

February 4, 1892 - Only one Everton

Just two days later The Football Association council passed the following resolution:

”That this council, in accordance with its past decisions will not recognise or accept the membership of any club bearing a name similar to the one already affiliated with the Association, and in the case of the Everton Club, will only recognise the actions of a majority of the members at a duly constituted meeting.”

Mahon and Clayton’s party were very much the majority, so the breakaway group heading for Goodison Road would take the Everton name with them and Houlding’s group would need to consider a new name.

The seeds for the new name were sowed on March 15, 1892, in the shadow of Anfield Road.

But not before one last blow had been landed.

On March 14, 1892 the Field Sports magazine reported: "A rumour has gained currency – by whom it has been set in motion I can only surmise – that Mr. John Houlding has endeavoured to injure Mr. William Clayton with his employer, Mr. Dwerryhouse."

Was the Lord Mayor of Liverpool really seeking to "beat up" his rival?

Given Field Sports' record of accuracy throughout the dispute perhaps we can safely dismiss this vicious slur.

On March 15, 1892 at a general annual meeting for members of the Everton Football Club, John Houlding was removed from the presidency of the club by voting.

Then the meeting was asked to vote on whether: “The Everton Football Club do now amalgamate with the Everton Football Club and Athletic Grounds Company, Limited.” That resolution was not carried by the members.

But Houlding saw the writing on the wall.

Some sources claim that he retired to his home at Stanley House, in Anfield Road, along with a number of close friends where William Barclay suggested that “their club” should be known as “Liverpool.”

There is no written evidence of this, but on June 3rd, 1892, Liverpool Football Club finally adopted their historic title.

The official change of name was declared in the correspondence from Companies House which stated: “Sir, With reference to your application of the 24th instant, I am directed by the Board of Trade to inform you that they approve of the of the Everton Football Club and Athletic Grounds Company, Limited, being changed to the Liverpool Football Club and Athletic Grounds Company, Limited .”

Everton and Liverpool had been born – and so had one of football’s bitterest rivalries.

The two clubs clashed for the first time just two years later.

They have been clashing ever since.