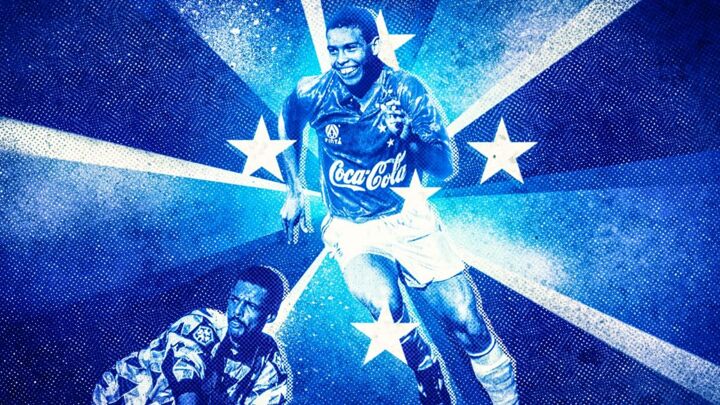

On a warm, spring afternoon at the Mineirao stadium in Belo Horizonte in November 1993, with Bahia’s away game against Cruzeiro in the Campeonato Brasileiro drawing to an end, Bahia goalkeeper Rodolfo Rodriguez knelt on the grass in his six-yard box, placed the ball on the floor, put his hands on his head and looked to the skies.

Rodriguez, an experienced Uruguay international, had already conceded five. Having just saved his side from a sixth, his gesture was a lament aimed at his fragile defence and a plea for mercy from the heavens.

Yet as he released the ball, there was one thing he had not accounted for. The 16-year-old boy stood a few steps behind him was not one for clemency. That boy had one thing on his mind and one alone: scoring goals. Rodriguez reached down, but the second the ball was unattended had been long enough. The goalkeeper grasped at thin air; it was gone.

With two long side steps, the adolescent in the dazzling blue shirt had nipped in. With his first touch, he had taken it away. With his second, he had poked it into the back of the empty net. Rodriguez stood up and appealed for some imaginary infringement, but it was too late. The embarrassment had already been inflicted.

Menino Ronaldo, the child soon to be the Fenomeno, had scored his fifth of the afternoon and Cruzeiro’s sixth.

“Ronaldo was a forward who was always paying attention to everything, he never gave up,” Rodriguez told Superesportes years later. Rodriguez found that out the hard way, and with Ronaldo’s eviscerating performance in that game, Brazil had woken up to the fact, too.

The next day, the newspapers in Belo Horizonte featured the grinning, buck-toothed teenager on their front and back covers and several of the pages in between. In Hoje em Dia, the headline read: ‘Brasil se curva aos pes do Ronaldo’ – ‘Brazil bows down at Ronaldo’s feet.’

Later that month, the teenage striker was called up to the Brazil squad for the very first time. The following year, he went on to win his first senior club silverware, was part of the Brazil squad that lifted the World Cup in Pasadena and earned himself a big-money move to PSV Eindhoven. But that game against Bahia is etched onto the Brazilian collective conscience as the moment Ronaldo announced himself as a superstar of the future.

The rise had been vertiginous, the time between anonymity and national fame flying past like Ronaldo flew past defenders with the ball at his feet. Ronaldo had only really taken his first step towards becoming a professional footballer three years prior to scoring five against Bahia in front of several thousand people in the ground and many more watching on television.

Ronaldo had always roamed the streets of Rio de Janeiro with a ball at his feet and, from the age of 12, he played for a futsal side called Clube Social Ramos. In his first season with the club, he took the local league by storm, scoring a record 166 goals.

But he had not played organised, 11-a-side football until he was 14, when he and his friend Alexandre Calango were taken in by Sao Cristovao, a club from the Rio de Janeiro neighbourhood of the same name.

Situated in the north of the city, Sao Cristovao’s stadium sits just a 20-minute walk from the iconic Maracana. Yet it possesses none of the glamour. Sao Cristovao now play in the lower reaches of the Rio de Janeiro state league system and in recent years have teetered on the brink of bankruptcy.

When Ronaldo joined in 1990, they were in a better position, playing in the top flight of the state league, but they were not giants of the Rio football scene by any stretch.

Importantly, though, the club’s facilities were situated relatively close to Ronaldo’s family home in the working-class Rio suburb of Bento Ribeiro, and Sao Cristovao’s coaches and directors were ready to give him the support he needed, an offer that was not forthcoming from the bigger clubs at which Ronaldo had had trials.

Alfredo Sampaio was the Sao Cristovao Under-17 coach when Ronaldo started playing for the Under-15s and remembers his arrival well. “He was being looked at by Flamengo,” Sampaio says, “but he had a lot of financial difficulties. He didn’t have money to go to training [on the bus] and Flamengo didn’t offer the help. That’s why he stayed with us.”

A Sao Cristovao director by the name of Ary de Sa – the same man who had made the deal with Clube Social Ramos to give some of their futsal players a chance to play on grass – provided a little financial assistance to Ronaldo and his family, as he did with other young Sao Cristovao players from less well-off families.

Ronaldo must have been devastated by the missed opportunity with Flamengo. It was the club he supported and, according to Sao Cristovao youth team colleagues, the club he loved so much he tried to avoid playing against them at youth level.

But at Sao Cristovao he was finally in a place where he could demonstrate the skill honed on the streets while skipping school, which he did much to the irritation of his mother Sonia dos Santos, who was vehemently opposed to her son’s footballing ambitions.

Even with Dona Sonia’s constant reprobation, Ronaldo was irrepressible. Sampaio immediately took note.

“I remember [the first time I saw him play] because it was a game soon after he’d arrived at Sao Cristovao,” he says. “It was a friendly tournament [with the Under-15 team] and he scored five goals in the game, if I remember rightly. He was really quick, he had really fast movement, a long stride, and that caught my eye.”

That one game was enough for Ronaldo’s rise to begin. He was soon playing for the Under-17 team coached by Sampaio, who was then promoted to coach the Under-20s. Though Ronaldo was still young enough to be playing for the Under-15s, Sampaio says he didn’t hesitate for a second to take Ronaldo with him onto that next rung of the ladder.

Despite his abundant talent, there was no pretension to Ronaldo, Sampaio recalls. The coach remembers a cheeky but pleasant young man.

“Generally, boys playing football in Brazil come from poor backgrounds, and you end up seeing some difficult behaviour because of the environment in which they live. But Ronaldo, no.

“His mother was always present in his life. He laughed and joked all the time. He didn’t have the resources to do the things that he might have liked to do, but in terms of behaviour and politeness, he was never problematic.”

Ronaldo’s youth-team strike partner Clayton Grilo remembers that they dreamed of playing against each other as professionals – Ronaldo for Flamengo and Clayton for Fluminense – and would listen to endless funk carioca, a genre of music that emanated from Rio’s favelas.

Clayton also recalls the pair skipping bus fares so they could save the little money they were given by the club for clothes, so they could look like their funk singer idols.

“Back in the day it was all that baile funk,” says Clayton, who went on to play for Gremio and Fluminense. “[Ronaldo] used to tell us that he’d go to the baile funk [dances] and get with loads of women, but he didn’t.

“He was ugly as fuck, who was he gonna get? He couldn’t fool us. Today he can get whoever he wants but in those days, with his big hair and sunburn, who was he going to get with?”

While a little disobedient, Ronaldo’s behaviour was nothing out of the ordinary for a teenager. There was one quirky element to the young Ronaldo’s personality that Sampaio noticed, however.

“He scored a lot of goals, but he never celebrated. He didn’t run off waving his arms. Once I asked him, ‘Why do you score goals and not celebrate?’ He turned around and said, ‘Gaffer, scoring is normal for me.’

“He didn’t say that with any arrogance, he wasn’t gloating, it wasn’t vanity. He said it with a childish air. It was more like, ‘If I celebrate every time I score, I’m going to end up getting tired.’ He was like that. He liked playing and having fun.”

So focused was Ronaldo on his own game, so absorbed in his own little world, that some tactical and technical aspects of the game passed him by completely. Sampaio remembers that if he wanted Ronaldo to mark a certain opposition player when Sao Cristovao were out of possession, it was not enough to refer to that player by his position.

If Sampaio said, ‘Press the centre-back,’ or, ‘Make sure you don’t give the deep-lying midfielder too much time on the ball,’ Ronaldo would look at him blankly. Instead, Sampaio had to point out the boy he wanted him to mark.

“What he wanted was to play. If it was against Pele or if it was against Joe Bloggs on the corner, it was the same thing.”

Ronaldo was also poor in the air, a deficiency he never corrected, which Sampaio puts down to disinterest. “He played across the world, but never was good at heading. He didn’t like it. He never developed the ability. The times that I met him afterwards, I joked, ‘Alright, have you learned how to head it yet?’”

Still, Ronaldo’s devastating pace, dribbling ability and unerring finishing made the other parts of his game irrelevant. “He did stepovers with one leg and the other,” Clayton Grilo recalls. “Nobody could catch him when he was running. That explosion was his essence.

“When we did physical training, the little rascal didn’t like to run at all. He came out with all the bloody excuses. But when it came to the game, the filho da puta transformed. In the game, he was the bollocks. It was natural for him, that acceleration, those stepovers with left and right.”

Even if it wasn’t yet clear that Ronaldo would become quite as good as he eventually did – “If I told you that I knew [at that time] that he would be one of the icons of world football, I would be lying,” Sampaio says – people other than the coaches at Sao Cristovao were starting to notice Ronaldo’s promise.

In a practice that was common in Brazil, emerging football agents Reinaldo Pitta and Alexandre Martins bought Ronaldo’s contract from Sao Cristovao for US$7,500. Sampaio had recommended that it would prove a wise investment. Likewise, national team scouts had started to sit up and take note of a boy who was making waves against some of the nation’s strongest sides at youth level despite playing for a relative minnow.

In January 1993, Ronaldo had just made another step up alongside Sampaio, who had been promoted to coach the first team. Yet before he could play for Sao Cristovao’s senior side, the 16-year-old was selected as part of the Brazil Under-17 squad that travelled to Colombia for the South American championships.

For the youth Selecao, the tournament was a disaster – they finished fourth and failed to qualify for an Under-17 World Cup for the first time in Brazil’s history. Yet for Ronaldo, it was another significant landmark on his road to superstardom.

In the first game, a Ronaldo hat-trick gave Brazil a 3-2 victory over Chile and further Ronaldo-inspired wins against Uruguay, Paraguay and Bolivia saw Brazil progress to the second stage – a four-team group that would decide the three nations to qualify for the Under-17 World Cup.

There, Brazil lost 2-1 to Argentina before struggling to 2-2 draws with both Chile and Colombia. The Selecao finished bottom of the group and the other three teams went to the World Cup later that year.

But Ronaldo had barged his way through opposition defences, scoring a total of eight by the time the tournament came to an end. It was sufficient for the next leg of his journey to begin.

Big clubs had already shown an interest in Ronaldo by then. Botafogo had offered agents Pitta and Martins 50% of a future transfer fee in return for Ronaldo’s signature, which Pitta and Martins rejected. Sao Paulo had also offered US$15,000, less than the US$25,000 the young agents were requesting prior to Ronaldo’s barnstorming displays with the Brazil Under-17s.

With that tournament fresh in the memories of the nation’s scouts, however, Ronaldo’s price had risen and Pitta and Martins went out looking for another suitor.

“There was an agent here called Leo Rabelo,” Sampaio says, “and Leo Rabelo was already prestigious in the eyes of Brazilian clubs. It was Leo Rabelo who intermediated with Cruzeiro, he opened the doors for Ronaldo and his agents.”

After negotiations, Pitta and Martins received US$50,000, a significant return on their US$7,500 investment. At the time, it was reported in the press that it was in fact Jairzinho, the 1970 World Cup hero and Cruzeiro legend, who had recommended Ronaldo to his old club, a story that has persisted.

In 2018, the 1982 World Cup final referee Arnaldo Cezar Coelho said on SporTV that it was Jairzinho “who polished Ronaldo, taught the runs, the acceleration, all those characteristics. And when it came down to it, the guys [agents] ignored Jairzinho, abandoned Jairzinho.” Jairzinho, sat alongside Coelho, refused to comment.

The next day, Pitta and Martins published a statement saying Coelho’s claims were false. Their version is that Jairzinho coached Sao Cristovao around that time but never worked with Ronaldo directly, and that Sampaio recommended Ronaldo to them, and they presented Ronaldo to Cruzeiro. Sampaio says the latter is “the only version” he knows.

It was the first soap-opera drama of Ronaldo’s career. The first of several. However it happened, the fact is Ronaldo became a Cruzeiro player. He made the journey 400km north to Belo Horizonte, the capital of Minas Gerais state, finally getting a shot with one of the nation’s biggest clubs.

Still just 16, Ronaldo was not put straight into the first team when he arrived. Instead, he trained and played with the Under-20s. He stood out again, of course, scoring four goals on his youth-team debut.

At that point, though, he was still one more extremely talented youth player in a country that produces them like the Cadbury’s factory churns out Dairy Milks. There were even arguments in Belo Horizonte bars about whether Cruzeiro or their local rivals Atletico Mineiro had the better up-and-coming centre-forward.

Atletico’s great hope was called Reinaldo, and Ronaldo and Reinaldo battled it out in the local Under-20 classicos and for the No.9 shirt in the Brazil Under-17 side. Reinaldo went on to have a good career, playing for Anderlecht in Belgium, Hellas Verona in Italy as well as a host of big Brazilian clubs. But as Reinaldo himself admitted after retiring, there was something extra special about his friend and rival.

“When [Ronaldo] came into the [youth] Selecao, I’d been there two or three years,” Reinaldo told Superesportes. “I always joked with Caio Ribeiro when Ronaldo came on in the second half, we already saw that one of the two was going to end up on the bench.

“I was only better than him at heading, but his finishing, I’ve never seen anything like it. He’d come on and it’d be stepovers this way and that.”

Less than three months after arriving in Belo Horizonte – three months in which Ronaldo found time to finish top scorer in the Minas Gerais Under-20 championship – Cruzeiro’s first-team coach Pinheiro saw fit to hand the awkward, skinny teenager his senior debut in a Minas Gerais state championship game against Caldense, which a Cruzeiro second string won 1-0.

In 2008, one of the Caldense defenders that day, Russo, told Hoje em Dia: “I really remember him on the pitch. He didn’t play very well.”

Ronaldo soon put that right. After a few more games back in the youth team and another tournament with the Brazil Under-17 team in the United States that served as a test event for the World Cup the following year – which nobody then expected Ronaldo to go to – he travelled to Portugal with the first team, who had recently won the Copa do Brasil.

Careca, a more senior Cruzeiro forward at the time, who now works with the club’s Under-17 team, says: “Cruzeiro went on a tour to Portugal and Ronaldo went as part of the touring party. By then it wasn’t Pinheiro as coach anymore. It was Carlos Alberto Silva.”

In Portugal, Cruzeiro played four friendlies, against Benfica, Belenenses, Penarol and Porto. Ronaldo played in all of them, scoring his first senior goal against Belenenses – with his head, ironically – and his second against Penarol.

“[Ronaldo] went really well at the tournament over there,” Careca continues, “played great games, scored goals, and he enchanted both the Portuguese and the manager Carlos Alberto Silva, who didn’t know who he was [before that]. When we got back, Carlos Alberto maintained Ronaldo in the first team. Then his story at Cruzeiro began.”

It nearly ended too, as it happens. Porto were so impressed that they offered Cruzeiro president Cesar Masci US$500,000 on the spot, 10 times what Cruzeiro had paid a few months prior. Masci said he wanted US$750,000 and Porto put an end to negotiations.

Porto’s reluctance to shell out that extra quarter of a million meant Ronaldo stayed in Brazil a little longer, giving him time to get to know the rest of the squad.

Careca remembers a happy-go-lucky character: “He was not at all shy. He was very extroverted, a big joker, joyful. His relationship with the other players was excellent.

“He was a boy who even at the beginning at Cruzeiro showed great potential technically. [But] what most impressed me about Ronaldo and what impressed me right from the start was his focus on becoming an idol and a great player.”

That focus, the ability to shut out the world and concentrate only on his game, is something others close to him comment on too. In Jorge Caldeira’s book Ronaldo: Gloria e Drama no Futebol Globalizado, Ronaldo’s coach from Clube Social Ramos, Alirio Carvalho says: “What was special about him was his attitude. It was as if he had come from the moon. Nothing disturbed him, nothing overawed him, nothing threw him off his game.”

Sao Cristovao coach Alfredo Sampaio says something similar: “If there was a time that he didn’t play as well, it was because of him, never because of the pressure of the game. He was never shaken by the occasion. He was like Garrincha. He didn’t care who he was playing against, he wanted to play. He trusted himself, and he was having fun.

“When he played against the best in the world, he played in the same way. He was always serene and tranquil, but always really quick, really decisive, very strong.”

That single-mindedness, combined with his speed, skill and strength, soon saw Ronaldo scoring goal after goal after goal for the Cruzeiro first team. It was already September by the time Cruzeiro returned from Portugal, but Ronaldo found the net 20 more times before the year was out.

Ronaldo scored against his beloved Flamengo, who were reigning national champions, netted twice against Botafogo, and managed eight in the Supercopa Libertadores.

In the round of 16, Cruzeiro beat Chilean league leaders Colo-Colo 9-4 on aggregate, Ronaldo scoring a hat-trick and setting up another in the first game and scoring twice more in the second leg.

In the quarter-finals, Ronaldo scored three against Nacional of Uruguay – once at home in a 2-1 loss, twice away in a 3-2 win – including a deliciously skilful goal to make it 2-0 and a last-minute winner to take the game to penalties. Cruzeiro were eliminated, but Ronaldo had already done enough to make himself the Supercopa’s top scorer.

That was swiftly followed by the five goals in that single game against Bahia in which Rodolfo Rodriguez suffered his embarrassing lapse late on – a game that was dissected and replayed on television for the whole of Brazil to see and resulted in Ronaldo’s first senior Selecao call up, though not a first cap.

Careca scored the only other goal that afternoon. “In that game,” he says, “[Ronaldo] showed all of his talent: mental, physical and technical. The only thing he didn’t do that day was make it rain in the Minerao. That’s when he started to grab the attention of the world.

“Playing with Ronaldo was really easy because his quality was so far above average. He played and made all the other players, all his colleagues, play and grow and give a better account of themselves. He made the game easier and did something that today is rare, he was a forward who decided games by himself. It came easily to Ronaldo.”

As he gained national fame for his goals, Ronaldo was already working on another part of his reputation in Belo Horizonte. He liked to sneak out of the digs where he lived with other players to hit the town and would sleep at Cruzeiro fans’ houses to get around the curfew imposed by the club. He was not a drinker, but, as Belo Horizonte-based journalist Paulo Galvao says, Ronaldo “was always a boy who people said liked two things: women and food”.

As part of an improved contract he earned while at Cruzeiro, club president Cesar Masci had given the young striker a red VW Gol that he used to get to and from training and go out in the city.

“I still lived in an apartment in the city centre in ‘93,” Galvao says, “and I was walking home one Sunday evening. There was a bus stop on the way and there was a guy [in a car] talking to a girl [at the bus stop, saying], ‘Come on, I’ll take you home, I’ll give you a lift. You don’t need to wait for the bus.’ She was saying, ‘No, no, no.’ When I looked closely it was Ronaldo.

“And at that time, for you to understand that in Brazil things weren’t really that serious, Ronaldo didn’t have a driving licence. Everyone knew [what he was doing], he went to training in his car. But he wasn’t 18, he wasn’t old enough to have a licence.

“But he had offers from other clubs, and to convince him to sign, the Cruzeiro president said, ‘Ah, no. Here, have a car.’ It’s Brazil. It’s different.”

Whatever he was getting up to off the pitch didn’t affect his form in the slightest. As 1994 dawned, Ronaldo kept hitting the net week after week, those legs a blur of stepovers, that blistering speed destroying defences left and right.

A hat-trick in a pre-season friendly against Jubilo Iwata in Tokyo introduced him to the audience in front of which he later starred in 2002, but the two displays that really grabbed the attention were both in the Mineirao, Cruzeiro’s cavernous home stadium, a ground on which he scored 32 goals in 27 games.

The first came in early March, when Ronaldo scored all three of his team’s goals in a 3-1 derby win over Atletico in front of almost 70,000 people under pouring rain. As much as for the goals, the game is remembered for a bit of skill that took him past Uruguayan centre-back Fernando Kanapkis.

“He destroyed the game,” says Careca. “He didn’t only destroy the game but he destroyed Kanapkis. He left Kanapkis sat on the floor. The Cruzeiro fans gave him a three-minute standing ovation.”

The second gala display was in the Copa Libertadores against Boca Juniors. Ronaldo had been kicked and fouled in the previous game between the two at the Bombonera, and if he went out for revenge, he got it. At 1-1 in the second half, he surged through two defenders, dribbled past another, rounded the goalkeeper and tapped the ball into the unguarded net to win the game.

The calls for Ronaldo to be handed a national team debut reached deafening levels and between those two games for Cruzeiro, Carlos Alberto Parreira heeded them. Ronaldo was included in the squad for a friendly with Argentina at the wild, vast, crumbling Arruda stadium in the north-eastern Brazilian city of Recife.

Ronaldo only got 10 minutes at the end after one of his childhood heroes Bebeto had given Brazil a 2-0 lead in the first half as Diego Maradona, who was trying to get in shape for the World Cup, watched from the bench. But Ronaldo’s cameo in front of 100,000 fans was what the nation desired.

As journalist Paulo Galvao says: “We have to remember that Brazil struggled to qualify for the World Cup in 1990 and in 1994. So there was that desire to see a player who really was out of the ordinary, who could swing the balance.”

Six weeks after that debut, Ronaldo was called up again for a friendly with Iceland in the southern Brazilian city of Florianopolis. The game was on May 3, exactly six weeks before the World Cup kicked off with Diana Ross’ infamous penalty in Chicago.

Romario and Bebeto were already guaranteed as the starting attacking duo in the USA, but Parreira was unsure of who else to take and against Iceland, he put Ronaldo in from the start, playing with the No.7 on his back alongside Corinthians forward Viola.

Thirty minutes into the game, a loose ball dropped on the edge of the area and Ronaldo was there. He hit it first time with his left foot and, after taking a slight deflection off an Icelandic defender, it nestled into the bottom corner of the goal.

Asked about the goal on Brazilian TV years later, Iceland goalkeeper Birkir Kristinsson chuckled and said: “I think [Ronaldo] was lucky because I would have saved it. I was going towards the left corner, but the ball deflected and went into the right corner. Obviously we could see he was a great player. We had trouble getting the ball off him.”

Ronaldo returned to Cruzeiro, scored two in the following two games and with it secured his first title as a player – the Campeonato Mineiro 1994, the Minas Gerais state crown. Unsurprisingly, he picked up another top-scorer gong to go with his medal, having hit 22 in 18 games.

All he could do now was wait as Parreira decided to whom those last few plane tickets would go.

The day of the announcement came and television cameras and radio reporters piled into Ronaldo’s living room along with him and his family. As Parriera read out the names and Ronaldo was among them, the cameras recorded the goofy, brace-filled smile that broke across his face.

The reaction was one of happiness, but not shock. Perhaps a phone call had been made to tell him the news in private beforehand, or maybe it was another example of his supreme confidence.

Despite the hype and hot air that surrounded Ronaldo, there was an understanding that he was going to the World Cup more for the experience than to be a real part of the team. Indeed, when in the US, he did not play a minute, watching from the bench as Romario’s goals secured Brazil their fourth world crown.

His selection, though, was confirmation that the future belonged to him.

After the tournament, he returned to Belo Horizonte, but everyone knew it would not be for long. Never one to sit still, Ronaldo was already looking ahead to his next move – he had said as much in the press. Even at such a young age, Ronaldo was already set on making rapid progress towards the very top.

There were plenty of admirers in Germany, Portugal and Italy, but Ronaldo chose the Netherlands and PSV. When asked why by a TV reporter, he said that Romario had recommended he sign for PSV. Ronaldo had responded, only semi-jokingly, by telling Romario that he would break his records in the Eredivisie.

Before he departed, Ronaldo had an inevitable parting gift. In his last game for Cruzeiro, a friendly against Botafogo, one of the clubs who had turned him down not long before, Ronaldo dribbled around the goalkeeper to score and earn his team a 1-1 draw.

Counting friendlies and competitive games, it was his 56th goal in 58 games for the club in a little over a year. As Careca says: “It’s not any old player who can do that.”

For Ronaldo, Cruzeiro received US$6million, 120 times what they had paid Pitta and Martins just over a year prior. “That was a lot of money for a club like Cruzeiro at the time,” says journalist Galvao. “It was enough to pay off all their bills and money they owed.

“Brazilian clubs suffer a lot, they’re always in debt. So $6million in ‘94, it was a lot. Nobody said, ‘No, they shouldn’t sell him.’ Maybe they could have asked to keep a percentage of a future transfer fee, but nobody complained about the fee.

“It was good business for both [Ronaldo and Cruzeiro]. He delivered on the pitch, he scored goals and won titles and brought money in.”

Good business, it seems, is also how Ronaldo viewed his time in Belo Horizonte. Asked if he is a club idol, ex-player Careca says yes, but Galvao says the word idol is too strong. Despite his success and the fond memories of those who played and lived alongside him, Ronaldo never created a particularly affectionate relationship with the city or club.

He never made any promises about returning to finish off his career there, nor does he talk about that period a great deal. That is not to say that the time spent at Sao Cristovao and Cruzeiro was not a crucial spell in Ronaldo’s formation as a player and man. It is instead, perhaps, a reflection on his character.

As Alfredo Sampaio and others who know him say, Ronaldo has always looked only ahead, on the pitch and in life.

“Ronaldo always put his career ahead of everything else,” Galvao says. “He never really cared where it was, or who he’s playing for. He cared about whether he was going to play and whether he was going to earn money. That’s the way he was since he was young.”

The attitude took Ronaldo to the very summit of the world game, saw him twice return from knee injuries that could have ended his career, and has made him a successful businessman too. Ronaldo now lives in Madrid, runs a renowned sports marketing agency and part-owns Real Valladolid, among other ventures. There is little time, one imagines, for reminiscence or social visits.

“I haven’t seen him for years,” Sampaio says. “The last time was in 2008. I was the manager of Vasco da Gama and we went to play a tournament in Dubai. He was there with Inter. Since that, I’ve only spoken to him once, through a television interview. He said I was the first person who believed in him as a player. His life is very busy but if I do meet him, he’s always very agreeable, we’ve always maintained a good relationship.”

Clayton Grilo, who now runs a social project called Centro de Oportunidade ao Talento that uses sport to help children from disadvantaged communities stay away from gangs and drugs, says it would be a dream if he could get his old mate to come and visit the kids he works with and that he hopes to make the visit happen at some point in the coming year. The kids would perhaps see something of themselves in Ronaldo’s story.

“He was a good lad, simple,” Clayton says. “He was a humble boy. Nobody expected he would become what he did. Each time he scored a goal or won a trophy I felt that I had played some part in his story. I felt happy with him.”

Sampaio concurs. “He was a normal boy,” he says. “He had his dreams.” With a leg up from Sao Cristovao and Cruzeiro, Ronaldo fulfilled them. In doing so, he fulfilled those of a nation too.