Phaedra Almajid recalls the day in early 2010 when three members of FIFA’s executive committee entered a hotel room in Luanda, Angola, to meet the team behind the Qatar World Cup bid.

As the media specialist for the campaign, Almajid had no inkling as to the motivation for the clandestine conversations. But when her colleagues offered each official a $1.5 million bribe in return for their vote, she could do nothing but guffaw at the brazenness of it all.

‘I just started laughing hysterically,’ says Almajid, flicking through her diaries from the time. ‘It was at that point I understood what was happening, that this was bribes. There was nothing extraordinary about the moment for those men. As a watcher, bystander, it was an extraordinary moment that I’ll never forget.’

Almajid, a whistleblower with whom The Mail on Sunday has worked extensively in the past, is speaking on the upcoming documentary The Men Who Sold The World Cup.

The two-part discovery+ feature, to which this newspaper has been granted extensive access, details the criminal lengths to which the Qataris went to ensure they hosted next year’s tournament.

As well as speaking to Almajid, former FIFA president Sepp Blatter and the chair of the Qatar bid team Hassan Al Thawadi — who denies any wrongdoing — the film-makers secured interviews with an FBI agent who helped to bring football’s ruling body to their knees and a British intelligence officer employed as a spy by England’s 2018 World Cup bid team.

Chris Steele, 57, was once an MI6 operative in Moscow and ran their Russia desk in London from 2006 to 2009. He then worked for England’s 2018 bid via his intelligence firm, Orbis, and learned of such high-level collusion between Qatar and Russia that he told the FA their hopes were doomed.

‘Vladimir Putin eventually realised that Russia’s 2018 World Cup bid was a prestige project, and required winning at all costs for political reasons,’ says Steele.

‘Modern Russia’s default mode is to engage in corruption and underhand dealings.’

Steele says collusion between Qatar and Russia began in earnest when Russia’s deputy Prime Minister, Igor Sechin, and Russia’s World Cup bid team all flew to Doha, Qatar in April 2010.

Steele’s sources told him Qatar would invest billions in a deal to develop oil fields on Russia’s Yamal Peninsula, and the two nations would do whatever necessary to gain support for each other’s bids to stage the 2018 and 2022 World Cups. Qatar’s Mohammed bin Hammam, a member of FIFA’s executive committee (ExCo) at the time, helped to broker this Doha pact.

‘The Yamal Peninsula deal, I think, says it all,’ says Steele. ‘This is how the operation was conducted and the sort of assets that Russia and Qatar brought to bear. The World Cup is bound up with the unseen way in which the world really works. Unseemly, I would say, and unseen.’

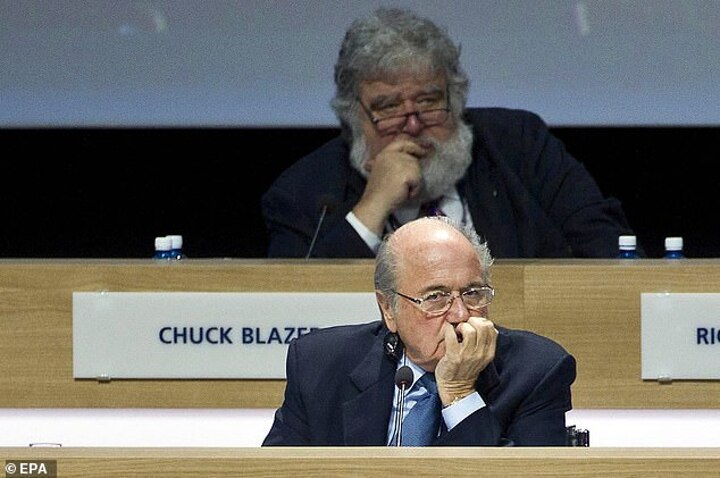

Steele went on to assist the FBI in bringing down FIFA, first, via intelligence he gathered during the 2018-2022 bid process; and second, with proof of corruption by another ExCo member, America’s Chuck Blazer.

That in turn, the MoS can reveal, had been provided to him via investigative reporter Andrew Jennings, who wrote about it in these pages in 2015 while not naming Steele.

‘Blatter was really the Godfather of a corrupt system that he had created and overseen,’ says Steele.

The extraordinary and suspicious events that unfolded in the votes for 2018 and 2022 were forecast in these pages before they happened and have been documented extensively here since.

On the last Sunday of November, 11 years ago, The Mail on Sunday published a special report, informed by Almajid — we protected her identity at the time — who predicted a little-known Middle Eastern state called Qatar was about to shock the world and win the right to host the 2022 World Cup.

‘The footballing heritage of Qatar, a lowly 113th in the game’s world rankings, is virtually non-existent,’ we wrote. ‘But the Qataris have used their petrodollar millions to gain power and influence in the game’s international circles.’

Almajid was quoted anonymously: ‘I don’t think Qatar will win 2022. I KNOW they will.’

And so it came to pass. On a fateful Friday in Zurich at the start of December 2010, one of the most corrupt sporting electorates in history — the 22 men who then comprised FIFA’s ExCo — voted to send the 2018 World Cup to Russia, and the 2022 event to Qatar.

In the intervening years, the MoS has repeatedly exposed the corruption and bribery that had festered behind the scenes in the 2018-2022 process, and barely anyone came out clean: not England’s 2018 bid nor the Spain-Portugal bid for the same year, nor South Korea’s for 2022, nor Australia’s.

England and Australia, for example, both effectively tried to bribe ExCo member Jack Warner, a notorious criminal from Trinidad, when unsuccessfully soliciting his vote. Spain meanwhile were in cahoots with Qatar over their own forbidden voting pact, and their bid leader was later censured for refusing to take part in an official inquiry into the matter.

But the most audacious episodes of vote-rigging and bribe-giving were delivered by shadowy forces working to make sure Russia 2018 and Qatar 2022 became realities — even as their official bid teams to this day insist they never engaged in any activities that were against FIFA rules.

Former FBI agent Michael Gaeta helped to gather evidence that millions of dollars of bribes were paid. ‘What has been revealed so far is a Mafia-style crime syndicate,’ says Gaeta, whose job, the viewer is told, was more typically to dismantle New York’s mob families. ‘My only hesitation in using that term is that it’s almost insulting to the Mafia.’

The hard evidence for the illicit payments include details of wire transfers of millions of dollars that were revealed in US indictment papers last year. Warner was said to have received a $5m bribe (£3.7m) to vote for Russia, funnelled via offshore accounts uncovered by the FBI and IRS, the United States tax authority, from shell companies connected to Russia 2018. Warner, who denied wrongdoing, is still fighting extradition to the US.

Warner’s ExCo colleague Rafael Salguero was offered a $1m bribe to vote for the same bid. The 2020 indictment papers also detailed how Nicolas Leoz of Paraguay (who died in 2019), Argentina’s Julio Grondona (who died in 2014) and the serially corrupt Ricardo Teixeira of Brazil, all ExCo members, received millions of dollars to vote for Qatar 2022.

An Argentinian sports marketing CEO, Alejandro Burzaco, who pled guilty to bribing many football officials, gave testimony that Grondona himself had admitted to him the Qatar 2022 bribery episode.

Other ExCo voters accused of improper conduct in relation to Qatar include Jacques Anouma of Ivory Coast, who has always denied receiving a cash bribe; Hany Abo Rida of Egypt, a close associate of Bin Hammam who once accompanied him on a trip to the Caribbean when $40,000 cash bribes were given to local football officials to support a FIFA presidential bid by the Qatari; and Worawi Makudi of Thailand, also on that trip and later banned from football for forgery and falsification of accounts. All three are believed to have voted for Qatar 2022.

At least four ExCo members from Europe are believed to have voted for Qatar 2022. Michel Platini of France, then head of UEFA, did so after French president Nicolas Sarkozy said it would be good for trade. Angel Maria Villar Llona of Spain did so after his country and Qatar made a vote collusion pact.

Marios Lefkaritis of Cyprus is alleged to have voted for them as part of a deal that saw his family sell property to Qatar for £27m, much higher than its value. He denies impropriety.

Vitaly Mutko of Russia, infamous for his key role in Russia’s state-sponsored doping, is believed to have voted for Qatar 2022 as part of the 2010 ‘Doha pact’.

Blatter himself recalls being shocked when he found out, ahead of the vote, that Qatar would win the rights to 2022. Asked if he believed that Qatar had paid bribes, Blatter says: ‘I don’t know if they paid, because I have not seen [details], but in football, to get the World Cup, everything is possible.’

Blatter says Platini called him a week before the December 2010 vote to tell him that at least four UEFA ExCo members including himself would be voting for Qatar despite knowing Blatter wanted the USA to host that tournament.

‘[Platini] told me: “Something has happened, now you will be in difficulties [as a USA bid supporter],’ says Blatter. ‘He told me four [UEFA votes] would go to Qatar, and that it was impossible for the USA to win. Platini lost courage, he should have said: “No, we’ll do something for the world and not something only for one country”.’

Blatter, though forced out of FIFA in 2015 and eventually banned from football following an investigation into a £1.3m payment to Platini, was never found guilty of wrongdoing around the World Cup scandal.

Towards the end of the documentary, however, the accusation is put to the Swiss administrator that he turned a blind eye to corruption to maintain a power base within the federation. After several moments’ thought, he says: ‘They are wrong to say I let them do it to maintain my power. We tried to stop that. It was not possible.’

‘The Men Who Sold the World Cup’ launches in the UK on October 21 on discovery+